Picador USA

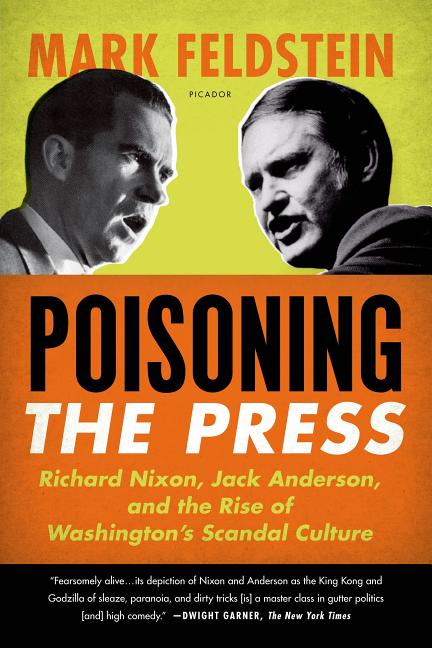

Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington's Scandal Culture

Couldn't load pickup availability

A Washington Post Best Book of 2010

A Denver Post Best Book of 2010

A Kansas City Star Best Book of 2010

Poisoning the Press recounts the bitter quarter-century battle between the postwar era's most contentious politician and its most reviled newsman. The struggle between Richard Nixon and Jack Anderson included bribery, blackmail, burglary, spying, and sexual smears--even a White House plot to assassinate Anderson. In this riveting, real-life political drama, Mark Feldstein traces the arc of this confrontation between a vindictive president and a flamboyantly crusading muckraker. Their vendetta at once symbolized and accelerated the growing conflict between the government and the press, a clash that would long outlive both men. Brilliant, captivating, and darkly comedic, Poisoning the Press is "an absolutely essential book for anyone interested in American political history" (NPR).

Share

Book Details

ISBN:

9780312610708

EAN:

9780312610708

Binding:

Paperback

Pages:

496

Authors:

Mark Feldstein

Publisher:

Picador USA

Published Date: 2011-25-10

View full details

Great story, needed a better author

In a recent written back-and-forth with author Mark Feldstein, I learned of his curious claim that the White House plotted to kill muckraking columnist Jack Anderson, and I was therefore anxious to examine his possible new evidence so proving.I was disappointed that there was none, and the author ignored clear contrary evidence, while instead resorting to a tired, tendentious anti-Nixon trope in service of the authors tidy narrative. A true murder plot never existed, and to the extent disabling poison was bruited about, it was the brainchild of the CIA, not the White House.But what I found, surprisingly, was a truly insightful look at the development of Watergate era “investigative” journalism. In a sharp distinction from his gullible acceptance of some anti-Nixon history, Feldstein takes his readers on a convincingly clear-eyed, page-turning romp through Jack Anderson’s development as a scandal-mongering columnist, all a necessary precursor to Watergate journalism. The link between Anderson’s reporting and Watergate journalism has been only superficially explored outside of Feldstein’s book, and so this work is important.In Feldstein’s detailed telling, Anderson worked hard, perhaps on occasions illegally, but always cleverly, to get the goods on politicians. His mentor Drew Pearson died in 1969, just as Anderson’s bete noire Richard Nixon was ascending to power, and it was a marriage made in muckraking heaven. Two of Anderson’s bigger expose’s were of the 1971 Nixon “tilt” toward Pakistan in its war with India, Pulitzer Prize winning reporting, and the earth-shaking (until Watergate) uncovering of the ITT bribery of the Nixon Administration, documented by the infamous memo of ITT lobbyist Dita Beard. The expose’s were strongly documented, and were not pushed beyond the limits of the evidence. They were, in short, solid pieces.Anderson and his predecessor Pearson never had been accepted by the mainstream media, which viewed their muckraking as beneath acceptable standards. To be sure, this allowed them a profitable syndicated column niche, and a monopoly on scandal-mongering: sources could go nowhere else.Just as the Pulitzer was giving Anderson a tincture of respectability, the Washington Post’s and its “Woodstein” journalism used this blossoming acceptance to push Anderson’s methods to the sidelines. Felstein brilliantly shows how Woodstein’s daily headline-grabbing likely forced Anderson (who mailed to his papers his typed columns four days in advance) to rush into print a premature claim that he possessed DUI citations for Democratic vice presidential nominee Thomas Eagleton. On his way in any case to marginalization, this huge mistake finished off Anderson as a credible finger-pointer.As thousands of wannabe Woodsteins poured out of schools, and every paper and local television network claimed to have “investigative” journalists, the result was thinly-sourced, lazy “infotainment.” Again, Feldstein displays thoughtfulness on this subject.He unwittingly and without self-consciousness, however, shows an even uglier result of this striving culture: political partisanship. Feldstein’s take on historical events is itself infected by this disease, which he is happy to limit to those with a “right wing” agenda, while unconsciously revealing his own leftist limitations.The most glaring example, one which renders incomplete his take on Anderson, is Feldstein’s rendition of the columnist’s foreknowledge of the Watergate burglary. He uncritically accepts Anderson’s story that he received a “tip” two weeks after the alleged March 30, 1972 approval of the Watergate burglary by former Attorney General John Mitchell. The tip didn’t pan out, Anderson claimed, so he published nothing. Sounds good so far.In another part of the book, Feldstein lightly treats Anderson’s having far earlier twice “misplaced” two detailed Watergate files, without exploring the full facts or stunning significance of them. In fact, well before John Mitchell allegedly told Jeb Magruder to burgle the DNC offices, not earlier planned by team leader Gordon Liddy, Anderson had been provided highly specific information by a minor New York muckraker about a planned burglary and wire tapping of the DNC. So? This corroborates the view that this burglary was planned by forces other than Mitchell or Liddy, and because of the intelligence demi-monde provenance of the information, revealed that the burglary was likely in part a CIA operation. Feldstein also inaccurately states that Lou Russell (a clear CIA asset of James McCord) was hired by the White House to infiltrate the Anderson office. The absence of evidence re Russell is glaring.With this background, the ominously threatening “Operation Mudhen” and subsequent Helms-Anderson lunch agreement is shown in another light, likely one forcing the columnist to back off the CIA’s illegal domestic operations. So did Jack Anderson really “misplace” two explosively detailed dossiers on a s...

Excellent

Mr. Feldstein has done a rather interesting story that puts an additional explanation of why RN became such a paronoid politician. By the time I had known about Jack Anderson. He had become a rather pitiful character. I had no idea of his impact in the early days and found the story informative and intriging. Its sometime easy to forget that in this age of instant "news" either real or imagined that JA was one of the forerunners of this kind of reporting. I found the chapter on JA making things up and then hoping they came true a little troubling. As if to say that someone would read his column and then fit the narrative to conform to it.The book is an interesting history of investigative journalism before there was such a term. To often the press of the day would sugarcoat things so as to not lose their sources. JA seemed to not really care about sensitivity to his sources because as Mr. Feldstein had pointed out he could get 10 more if he wanted to.In the end as is so often the case JA fell into the problem that most great or significant people fall into. He stayed in the game to long and as a result his significance diluted to the point of inconsequence.I give this read 3 stars. The reason for that is the authors repetitive use of the word muckracker and the somewhat stale ending of his career. At the very least I now understand why Brit Hume is the way he is

Your enjoyment of Mark Feldstein’s POISONING THE PRESS will depend on your appreciation of political minutia. Feldstein’s book covers the similarities – and differences – in Richard Nixon and Jack Anderson, at the time a well-known muckraking columnist. The two men, one a Quaker and one a Mormon, both have hardscrabble lives out west with disappointing fathers; both serve in WWII and both head to Washington in the post-war headiness documented in so many biographies of similar men. Anderson gets a job working with columnist Drew Pearson, Nixon, after the Alger Hiss case, gets the vice presidency. And then the dance starts between the two men, with Anderson’s ability to get top secret documents and Nixon’s frustration at being able to stop him. The book naturally peaks in the pre-Watergate scandals, such as the India-Pakistan skirmish, Dita Beard and the ITT memo and the government’s interference in the Chilean election. Feldstein’s immaculate research, complete with a length notes section, lives no minute fact unchecked in his coverage of this now obscure scandals. With a cast of characters such as J. Edgar Hoover, Brit Hume, Eisenhower and the President’s Men, Feldstein has delivered a nice portrait of these mid-century titans while he never really explains the title of his lengthy thesis.